China and U.S. Air Traffic Picks Up, but Sits Well Below Pre-COVID

Dion Zumbrink

September 13, 2023

© Kayla Kozlowski / Unsplash

In August, the United States and China reached an agreement to increase air traffic between their countries to twice the number of passenger flights currently permitted. From September 1, the round trips allowed increases to 18 weekly and from October 29that rise again to 24 per week—up from the current 12.

To date, the number of direct passenger flights between China and the U.S. has remained very low. An important factor to this is the ban for American carriers to overfly Russian airspace, resulting in rerouting and much longer flight times.

International air traffic in China has been catching up since January 8 when the country reopened its borders and most of the remaining travel restrictions related to the COVID pandemic were removed. By April this year, international flights to China had reached 34% of their 2019 levels.

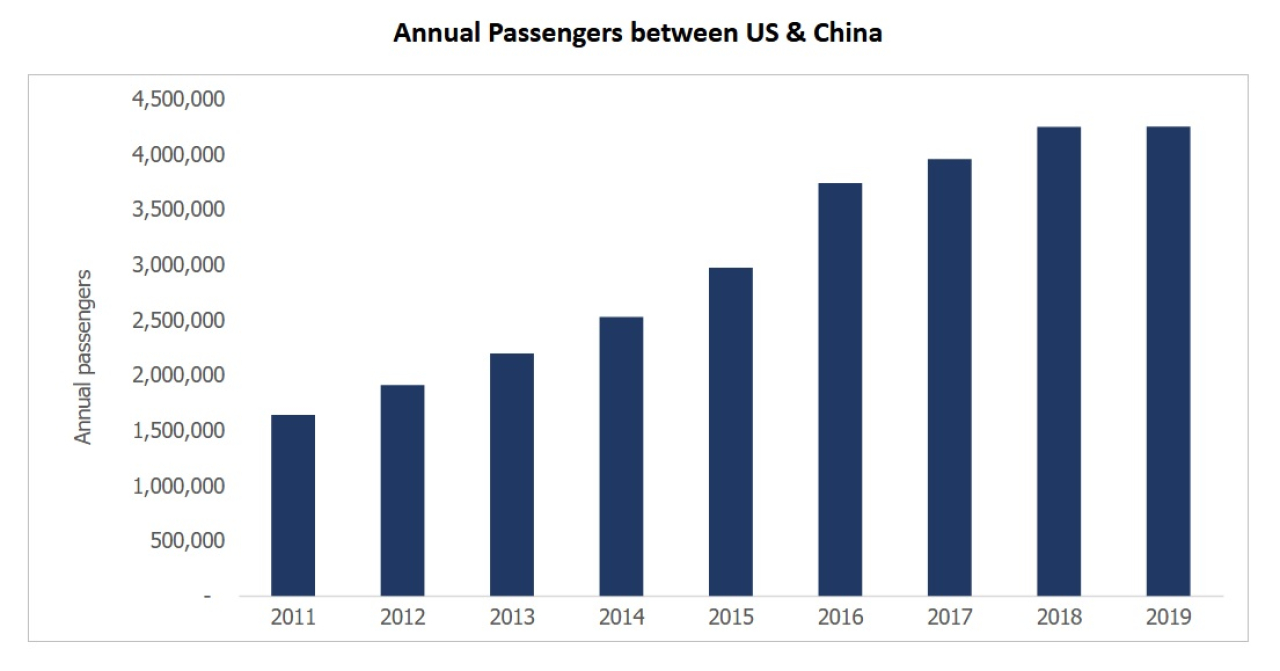

Growth was consistent pre-pandemic.

© Dion Zumbrink

While international traffic, and in particular to the U.S. has lagged behind domestic, overall China air traffic recovery is in line with the recovery seen globally. According to statistics from China’s civil aviation authority, CAAC, in the first half of 2023, about 284 million air passengers were handled at Chinese airports, which is 88% of the level recorded in the first half of 2019.

In contrast, U.S. traffic from China is only operating at around 6% of 2019 levels while traffic between China and the UAE has already hit over 60%, and to neighboring Thailand and Korea, as well as the UK, it has reached just under 40%. Even after doubling the number of flights, the China-America traffic flow will be lucky to top out at 10% of its pre-pandemic level by the end of this year.

Pre-pandemic Traffic Flows Were Strong

Analyzing the traffic flow pre-pandemic, traffic between the U.S. and China had been growing well. China was 7th place overall in foreign destinations from the U.S. growing from 1.6 million annual passengers in 2011 to 4.2 million by 2019.

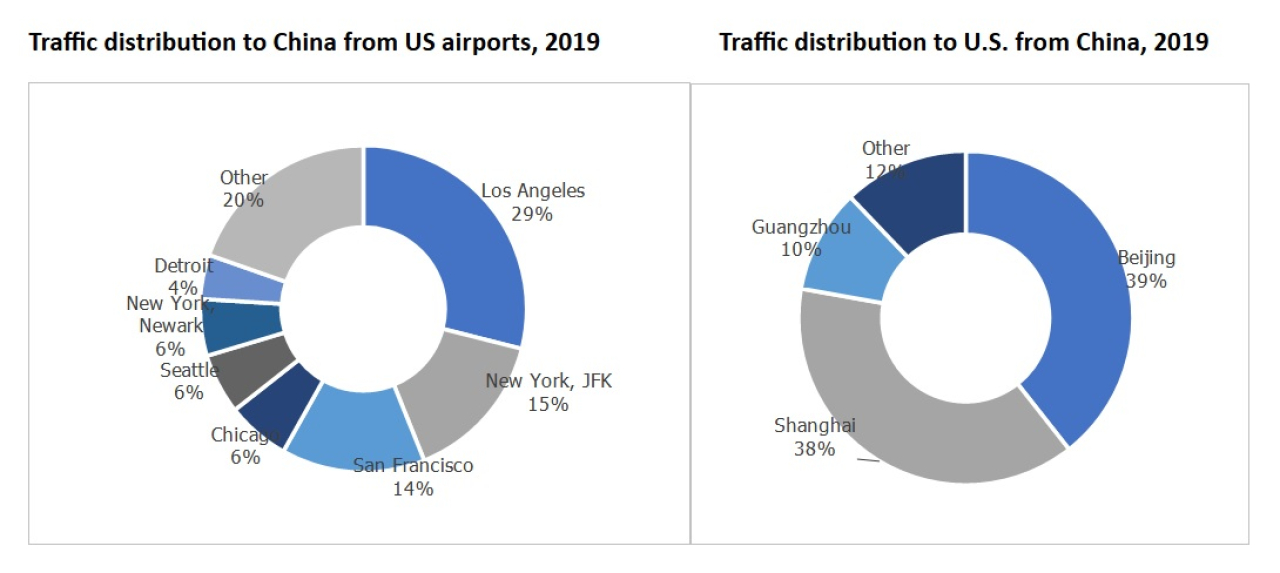

West-coast airports were dominant for Chinese traffic while in China just two hubs funneled most U.S. departures.

© Dion Zumbrink

The main ports of entry (based on 2019 data) were Los Angeles, New York JFK, and San Francisco. In Los Angeles, the traffic to China grew particularly strongly over a decade, quadrupling between 2011 and 2019 with extra/new service from Delta Airlines, Xiamen Airlines, Hainan Airlines, and Sichuan Airlines commencing between 2015 and 2017, in addition to the five airlines already operating. On the Chinese side, nearly 90% of traffic went to three main hubs: Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou.

Nine airlines were active in the market in 2019 but, post-pandemic, they have mainly deployed their capacity in other markets. Most passengers were carried on Chinese carriers.

Chinese carriers are more dominant on the U.S.-China route.

© Dion Zumbrink

Rebound Difficulties

New slot allocations will likely first boost traffic from U.S. west-coast airports. Also in the foreseeable future, considering that for American-based airlines, routes from the eastern part of the country to China will need a significant rerouting to bypass Russian airspace.

Air China and China Eastern Airlines are the only airlines to have resumed flights to New York so far as they do not fall under the restrictions. However, even the routes from the west coast cross Russian airspace in the most optimum path, so Chinese airlines continue to have a competitive advantage over their American counterparts in this market for the time being.

While the Chinese market was not among the largest for international air traffic in the U.S.—for example at New York JFK airport in 2019 it only constituted less than 5% of total international traffic—Chinese passengers tend to spend more at airports.

A return to the pre-pandemic trend would therefore be very welcome for U.S. airports. It seems, however, that with the ongoing geopolitical conflicts and related air routing issues, in addition to a slowing Chinese economy, a full recovery of this market is not likely in the near future.