Canadian Airports in the Eye of the Pandemic Storm (Part 2 of 2)

Frode Skulbru

September 16, 2020

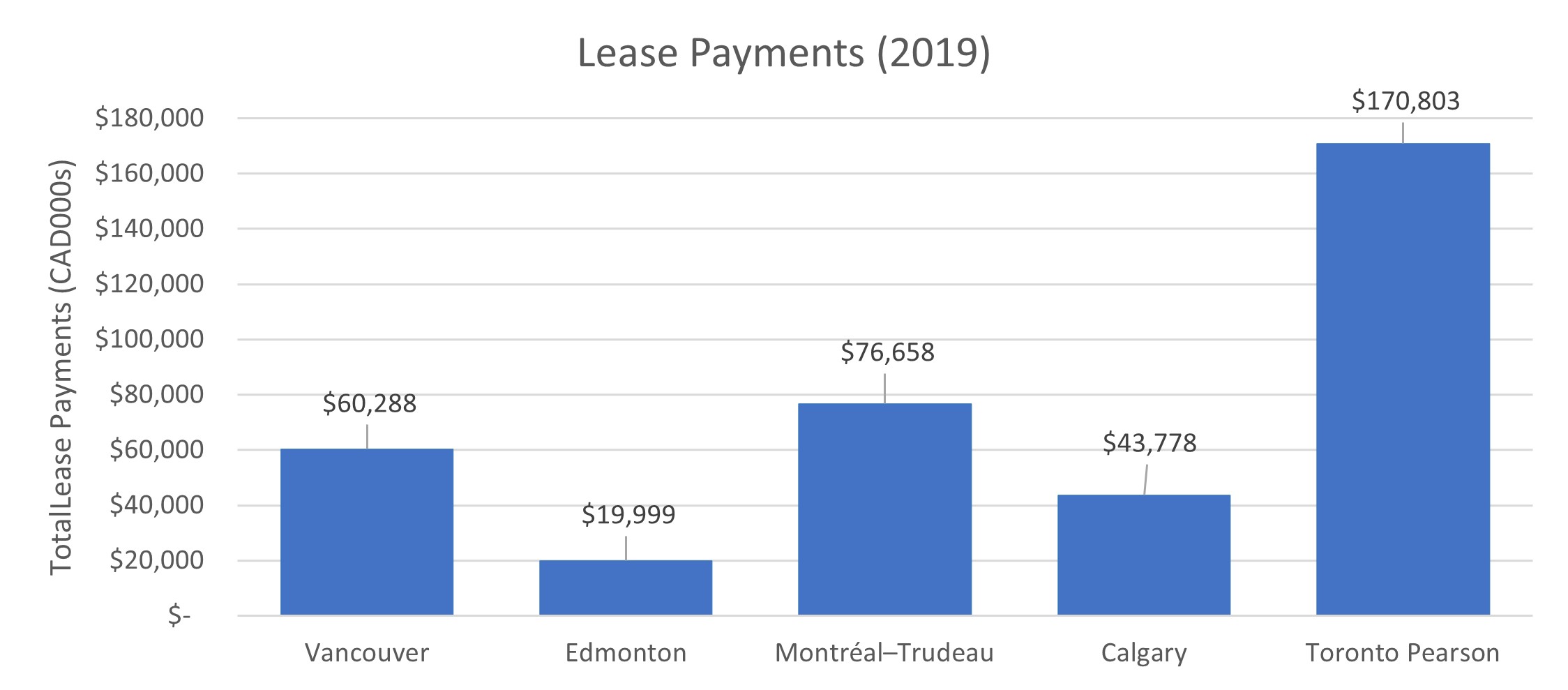

Part one of this article can be seen here (opens in new window) A Perfect Storm With passenger growth year after year, the outlook was very rosy going into 2020. Passenger volumes were way up, additional long-term capital programs were planned, and finances were, for the most part, in order. Then March came and it all came crashing down. A “perfect storm” is often used to express a situation where Murphy’s law comes into full effect, in other words, everything that can go wrong is precisely doing that. Airports are (or at least have been) attractive investment targets partly because of the many revenue streams it offers. The diversified client base is also an attractive attribute – if one airline struggles another can and will fill the void if the market is there to support the service. These days, there is no market. All sources of income have been reduced to a trickle. As a consequence, variable expenses were dramatically reduced, mostly through staff reductions. As an example, YYZ made approximately 500 jobs redundant in July 2020, representing a reduction of 27 per cent of its workforce. YYZ is also particpating in the Canadian Emergency Wage Subsidy (“CEWS”) program, thereby receiving wage subsidies from the Government. Rent obligations to Ottawa remained until March 30th, 2020, when then Finance Minister Bill Morneau announced that the government is waiving ground lease rents from March 2020 through to December 2020 for the 21 airport authorities that pay rent to the federal government. Smaller regional Canadian airports were not mentioned!  Cash is King as Debt Still has to be Serviced While some expenses can be reduced, debt service remains unless one can re-negotiate terms with the lenders. Bonds can ingeneral be more difficult to re-negotiate as these are usually held by a variety of investors. In the case of Calgary and Edmonton, the Province of Alberta holds most of the debt. Canada’s airports owe collectively over $15 billion, estimated to be more than the combined provincial debts of Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland & Labrador. One a positive note, airports like Victoria, Charlottetown, and Saskatoon are close to debt free.

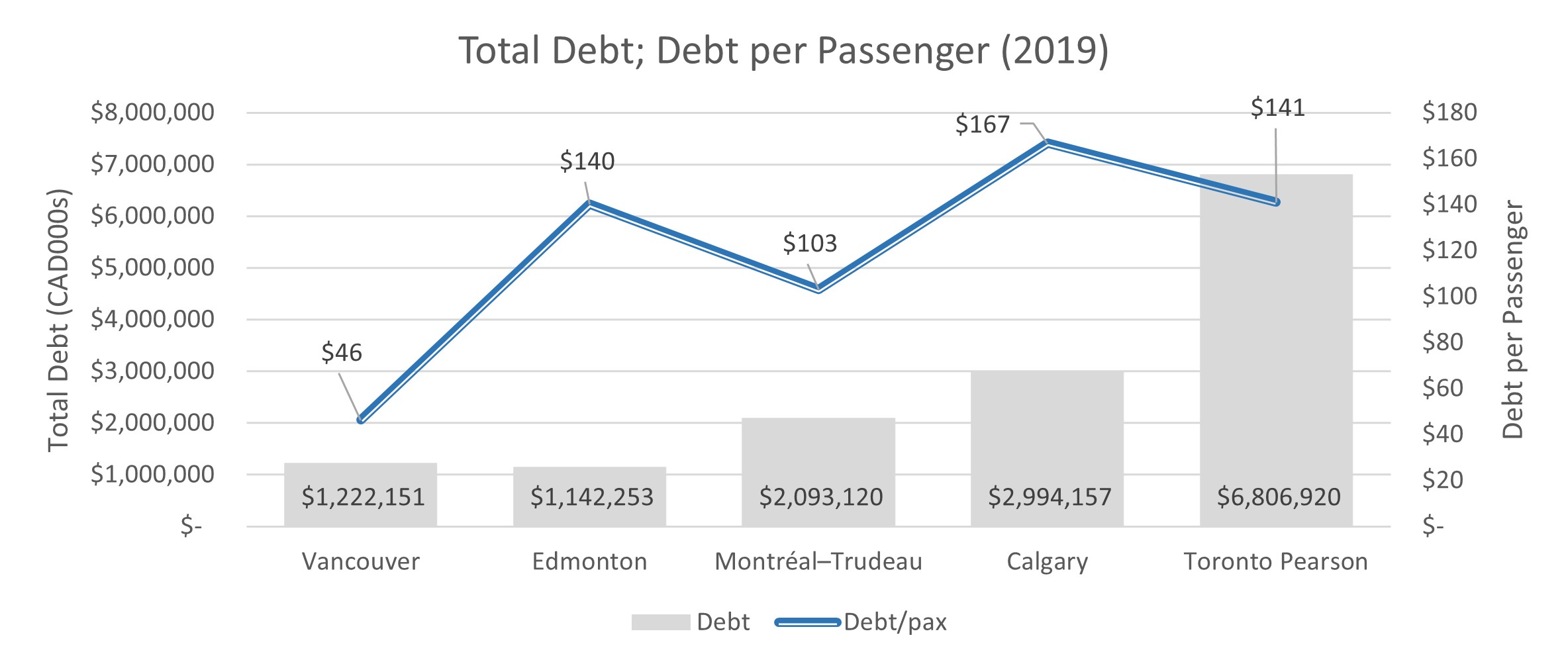

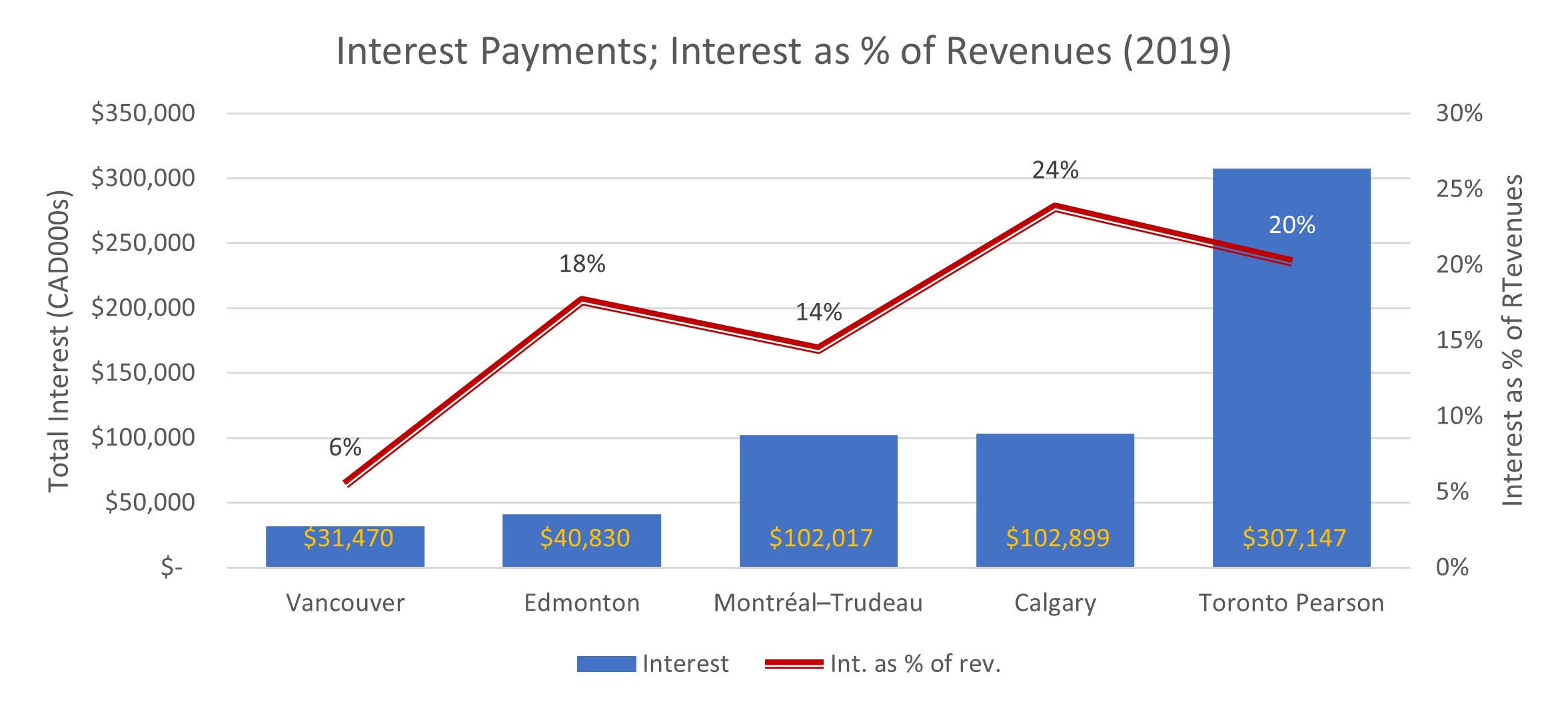

Cash is King as Debt Still has to be Serviced While some expenses can be reduced, debt service remains unless one can re-negotiate terms with the lenders. Bonds can ingeneral be more difficult to re-negotiate as these are usually held by a variety of investors. In the case of Calgary and Edmonton, the Province of Alberta holds most of the debt. Canada’s airports owe collectively over $15 billion, estimated to be more than the combined provincial debts of Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland & Labrador. One a positive note, airports like Victoria, Charlottetown, and Saskatoon are close to debt free.  As the graph above illustrates, Toronto-Pearson (YYZ) has the most debt of the top five at $6.8 billion. On a per passenger basis we can see that YYZ’s debt is three times larger than Vancouver’s (YVR). YVR has by far the lowest debt per passenger at $46 (debt in this context is defined as all liabilities on the balance sheet). Most of the total debt is of course long term, hence the immediate focus is the management of annual debt service, i.e. interest payments. The below graph reflects the 2019 payments as reported in the airport’s annual reports (bar) and the percentage of revenues these represent (line). With the full 2019 revenues in place, we see a wide range from 6% at Vancouver to 24% at Calgary. While interest as a portion of revenues alone do not fully illustrate the ability to service debt, it reveals an accute need for additional liquidity if the percentage is high.

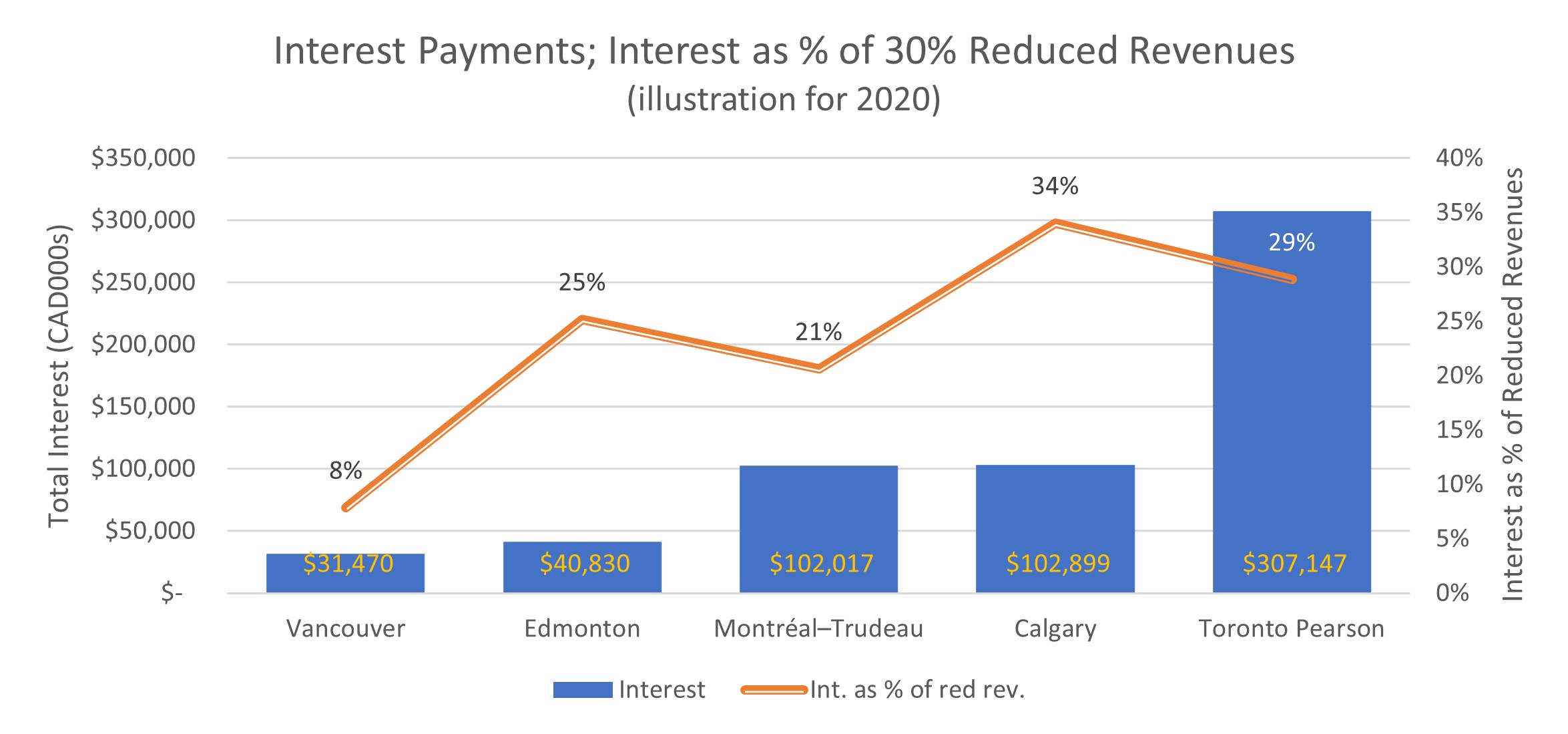

As the graph above illustrates, Toronto-Pearson (YYZ) has the most debt of the top five at $6.8 billion. On a per passenger basis we can see that YYZ’s debt is three times larger than Vancouver’s (YVR). YVR has by far the lowest debt per passenger at $46 (debt in this context is defined as all liabilities on the balance sheet). Most of the total debt is of course long term, hence the immediate focus is the management of annual debt service, i.e. interest payments. The below graph reflects the 2019 payments as reported in the airport’s annual reports (bar) and the percentage of revenues these represent (line). With the full 2019 revenues in place, we see a wide range from 6% at Vancouver to 24% at Calgary. While interest as a portion of revenues alone do not fully illustrate the ability to service debt, it reveals an accute need for additional liquidity if the percentage is high.  At YVR, traffic until the end of July was down just over 60% compared to 2019. At YYZ, passenger activity decreased 58.6 per cent during the first six months of 2020 as compared to 2019. At the same time, at YYZ revenues declined by approximately 30% the first six months. Using this as a proxy for the revenue generation for all the top five airports, we have reduced revenues by 30% in the graph below.

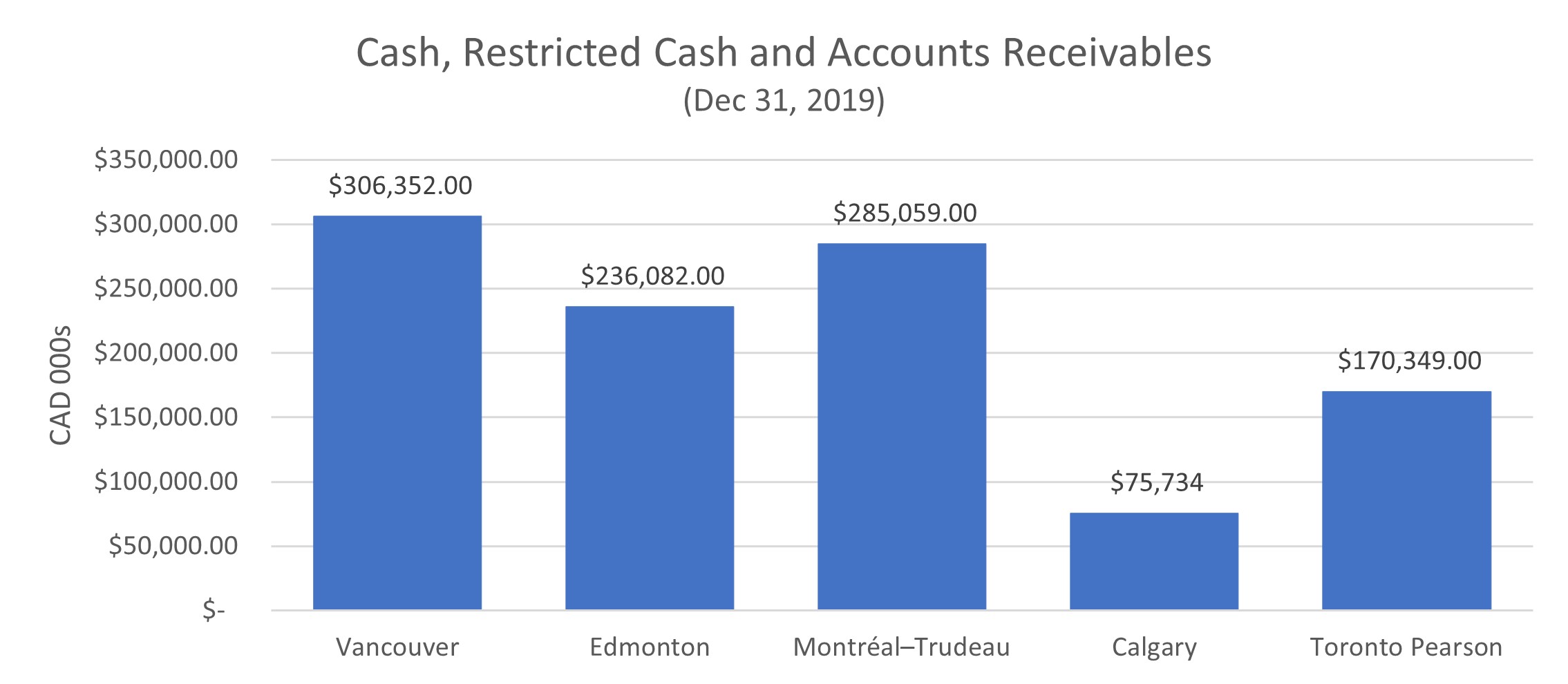

At YVR, traffic until the end of July was down just over 60% compared to 2019. At YYZ, passenger activity decreased 58.6 per cent during the first six months of 2020 as compared to 2019. At the same time, at YYZ revenues declined by approximately 30% the first six months. Using this as a proxy for the revenue generation for all the top five airports, we have reduced revenues by 30% in the graph below.  Assuming the same interest payments due this year as last year, YVR seems to be still in good shape with 8% of revenues going to service its debt. Calgary (YYC) and Toronto on the other hand will now have to use around 1/3 of its revenues for debt service alone. A tall order, knowing that Calgary posted a net loss in 2019. Even accounting for $169 million in 2019 depreciation (as these are non-cash items) and $44 million in forgiven lease payments, the picture is pretty bleak. YYC administrators say they will need to borrow another $250 million just to keep planes flying in and out of the city for the next couple of years. Cash is king these days, hence a solid short term liquidity is crucial. The following depicts the cash, restricted cash (mostly debt service reserves) and accounts receivables of the five sites as at December 31, 2019.

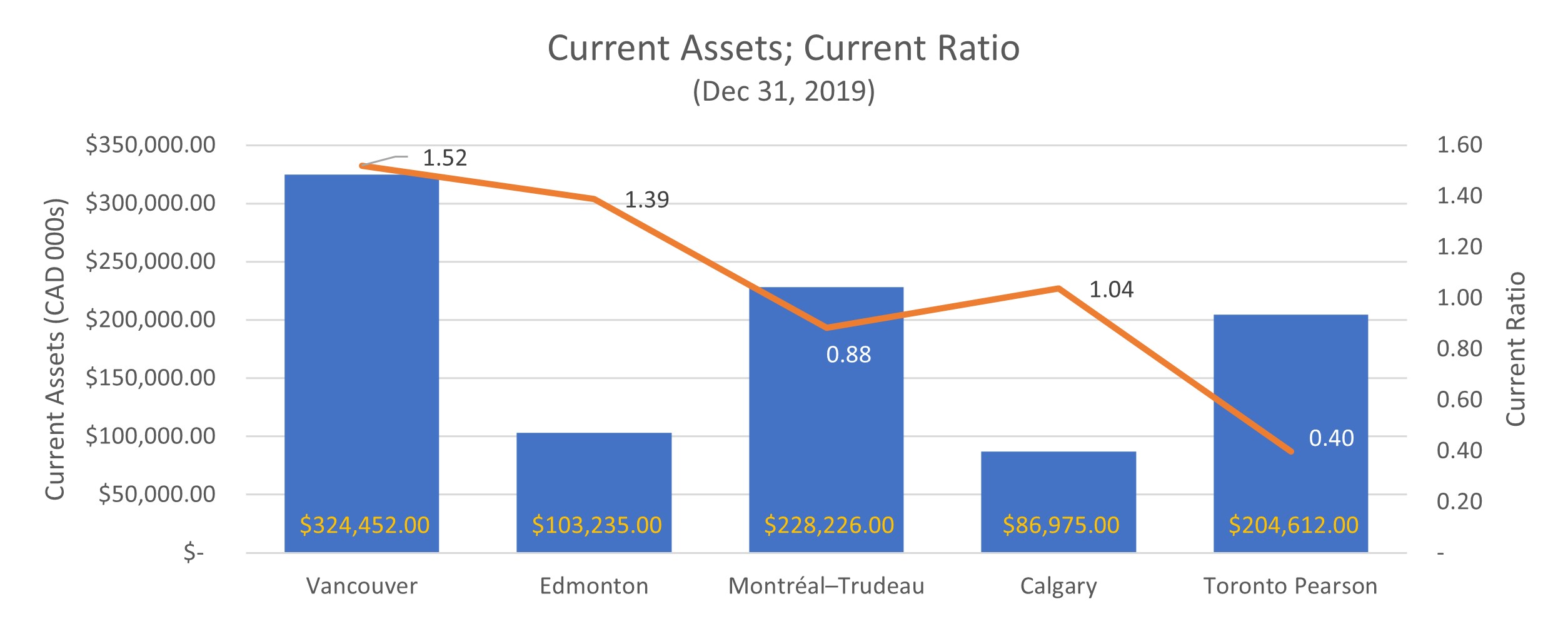

Assuming the same interest payments due this year as last year, YVR seems to be still in good shape with 8% of revenues going to service its debt. Calgary (YYC) and Toronto on the other hand will now have to use around 1/3 of its revenues for debt service alone. A tall order, knowing that Calgary posted a net loss in 2019. Even accounting for $169 million in 2019 depreciation (as these are non-cash items) and $44 million in forgiven lease payments, the picture is pretty bleak. YYC administrators say they will need to borrow another $250 million just to keep planes flying in and out of the city for the next couple of years. Cash is king these days, hence a solid short term liquidity is crucial. The following depicts the cash, restricted cash (mostly debt service reserves) and accounts receivables of the five sites as at December 31, 2019.  Expanding the above to include all current assets (bars), the Current Ratio can be calculated as depicted by the line graph. Vancouver and Edmonton seem to be in best shape to weather the storm in the short term, whereas Toronto with a 0.4 ratio will need additional liquidity in short order (see below for the plan in place to achieve this).

Expanding the above to include all current assets (bars), the Current Ratio can be calculated as depicted by the line graph. Vancouver and Edmonton seem to be in best shape to weather the storm in the short term, whereas Toronto with a 0.4 ratio will need additional liquidity in short order (see below for the plan in place to achieve this).  Ability to Raise New Capital Due to its legal structure as not-for-profit corporations, unlike regular corporations, Canadian airports cannot raise additional capital through the issuance of shares, nor can they reduce dividend payments as there are none. Increases in Fees and Charges, a regular occurrence in the past, will not help either as there are there are far too few flights and passengers to pay for such charges. Additional debt, if possible, would only further increase the problem of over leverage, but this is the only approach in the short term in lieu of a complete Government buy out.

Ability to Raise New Capital Due to its legal structure as not-for-profit corporations, unlike regular corporations, Canadian airports cannot raise additional capital through the issuance of shares, nor can they reduce dividend payments as there are none. Increases in Fees and Charges, a regular occurrence in the past, will not help either as there are there are far too few flights and passengers to pay for such charges. Additional debt, if possible, would only further increase the problem of over leverage, but this is the only approach in the short term in lieu of a complete Government buy out.

YYZ Plan and Approach An illustration is Toronto’s reported plans. As at June 30, 2020, YYZ has unrestricted cash of $231.6 million (i.e. higher than at year end, hower it was not reported where the additional funds come from) and available undrawn committed credit under its Operating Credit Facility of $875.0 million for total available liquidity of $1.1 billion. To ease requirements related to debt service, on July 27, 2020 YYZ successfully completed an amendment to the Corporation’s Master Trust Indenture (“MTI”). The MTI amendment temporarily waives the company from complying with its rate covenant prescribed under the MTI for fiscal years 2020 and 2021. finally, the airport extended its committed revolving operating credit facility in July 2020 by an additional year to May 22, 2023.

In the short term, increasing debt will keep the doors open and the lights on but with a $90 million net loss for the first six months and a rapidly increasing debt load as reported in Toronto, speculation will soon commence about the impact on passenger fees and srvice levels. Over the longer term and once the pandemic is no more, the current Liberal Government (if they remain in power) may find it more attractive to offload the airports to the private sector and collect a windfall payment, rather than facing becoming the de-facto owner of the operating companies (i.e. Airport Authorities) yet again. There are legal roadblocks that may slow the process, however the higher the subsidies from the government , the firmer it may be in its quest to recover some of this. Ownership Models One would think that a future change of ownership and governance would take Canada towards the right of the below graph as they came from the left under the Transport Canada ownership pre-90s. The current Airport Authority structure fits somewhere in the middle, neither government nor private.  A traditional PPP or concession model may be used, but this may not be the most appropriate as much of the advantages brought by private sector airport specialists are already in place. An alternative would be several tranches of (financial) transactions to ensure one or several large-scale investors holds a substantial stake before the rest is sold to the public. Examples of this approach include Mexico where its commercial airports were grouped in three bundles, partially sold to companies with operating credentials before a further stake was taken public (NYSE). In Spain, 49% of AENA has been listed since 2015, with the majority owned by the State. The French regional airports are governed by yet another model where local and federal government-entities own a portion of the airport management companies with the rest held by strategic investors, all under long term ground leases. As the State would continue to own the land and fixed assets, there should be no need for it to also own a part of the management company. As the Airport Authorities are established organisations with a long track record, it could be possible and feasible that they be allowed to capitalize and bid on their own airports – this time as corporations with key investors as shareholders.

A traditional PPP or concession model may be used, but this may not be the most appropriate as much of the advantages brought by private sector airport specialists are already in place. An alternative would be several tranches of (financial) transactions to ensure one or several large-scale investors holds a substantial stake before the rest is sold to the public. Examples of this approach include Mexico where its commercial airports were grouped in three bundles, partially sold to companies with operating credentials before a further stake was taken public (NYSE). In Spain, 49% of AENA has been listed since 2015, with the majority owned by the State. The French regional airports are governed by yet another model where local and federal government-entities own a portion of the airport management companies with the rest held by strategic investors, all under long term ground leases. As the State would continue to own the land and fixed assets, there should be no need for it to also own a part of the management company. As the Airport Authorities are established organisations with a long track record, it could be possible and feasible that they be allowed to capitalize and bid on their own airports – this time as corporations with key investors as shareholders.